Under the Impression. Valery Geghamyan

The Secret of Art is Impression.

— Valery Geghamyan

When it comes to comprehending and presenting the heritage of an extraordinary person, it is very tempting to set foot on the wide tract of traditional pathos, break into a boring song about “overlooked a genius”, and thus quickly turn a really worthy person into a smoothed image, ready to be sold for a saleable penny on a market day.

In art as in life there are no concepts "right - wrong". There is no perfect example of worship to the art, there are no criteria for this worship. There are great artists, crowned with laurels, there are no less great, unknown in life and forgotten for centuries or forever. This does not mean anything. Nobody knows how it should be, everyone has their own path.

For some, Valery Geghamyan is an outstanding artist and teacher, an enlightened hermit who possessed a rare ability to protect and defend his inner world. For others, he is an eccentric and misanthrope with many complexes who has never learned to communicate with the world painlessly for him. To others he is completely unknown.

However, all features are correct and in no way are mutually exclusive. Eighteen years after his death the time has probably come without unnecessary epithets, to try to realize WHO and WHAT was it in Odessa in the sixties and nineties?

But Odessa happened later.

Born into a very difficult family Valik Geghamyan did not exactly draw out a lucky ticket, but the direction of his development was set. The ancient clan endowed the child not only with many talents, but also, despite the repression of family members and a modest way of life, was still able to provide the proper social circle. Leading representatives of the intellectuals were regulars at the Ter-Melik Sitsianov house and had a serious influence on Valik formation. In particular, Aram Khachaturian drew attention to the musical abilities of young Geghamyan who, by the way, at that time was thinking about a musical career. Music, visual arts and architecture are always close by. It was not for nothing that Leon Battista Alberti rediscovered the theory of harmony in the 15th century receiving visual lessons precisely from the laws of music.

Valik Geghamyan was also gifted in literature. It is known that as a teenager he wrote stories and illustrated them himself.

After graduating from school in 1940 the young man entered an art school and there began a new stage in his life associated with Martiros Saryan, by that time already an Armenian and Soviet legend. The artist was not just a teacher for Valik, he became his informal guardian, in fact, a member of the family. Coming to the plein airs in Garni, Saryan stayed at the house of Ter-Melik Sitsianov. Valik Geghamyan was close friends with Saryan's eldest son Sarkis, later a famous literary critic, specialist in Armenian and Italian literature of the Renaissance. Sarkis often took Valik to lectures, so he had the opportunity to attend university courses in philosophy, history, literature, while still a schoolboy.

In 1945 Geghamyan went to the newly organized Yerevan Art Institute and, of course, Saryan's workshop. Around this time he began to keep a kind of a diary. He carefully brought in it the brightest impressions of reality, reflections on the nature and mechanics of art, characteristic images, sketches of future works and even not bad sketches of three stories.

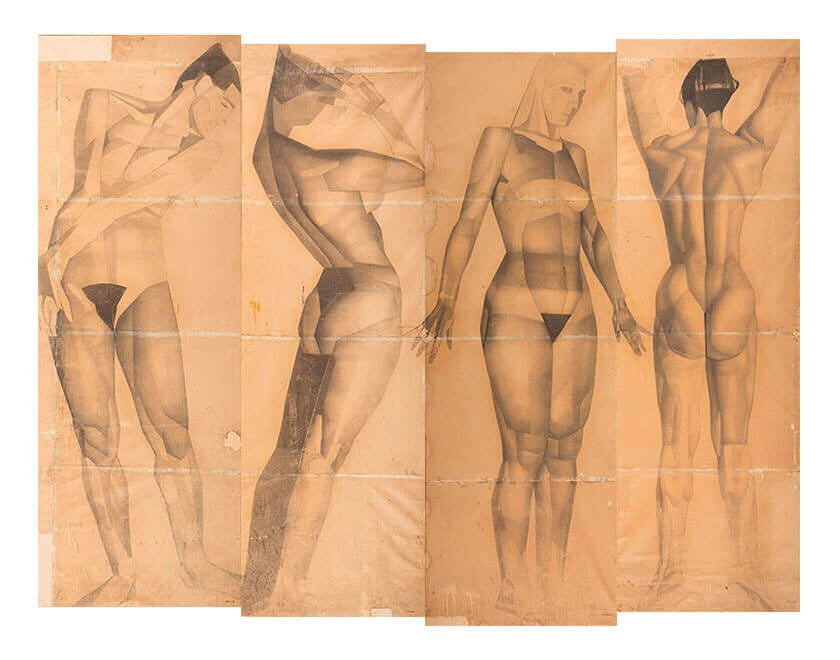

Polyptych #016-#019

Translating a seventy-year-old manuscript in terrible handwriting in Armenian is not an easy task, but it was worth it. The diary turned to be a unique document that refuted the hitherto existing versions of the artist's formation. The traditional scheme “studied, got hold of, developed, transformed and finally - here I am” does not work with Geghamyan.

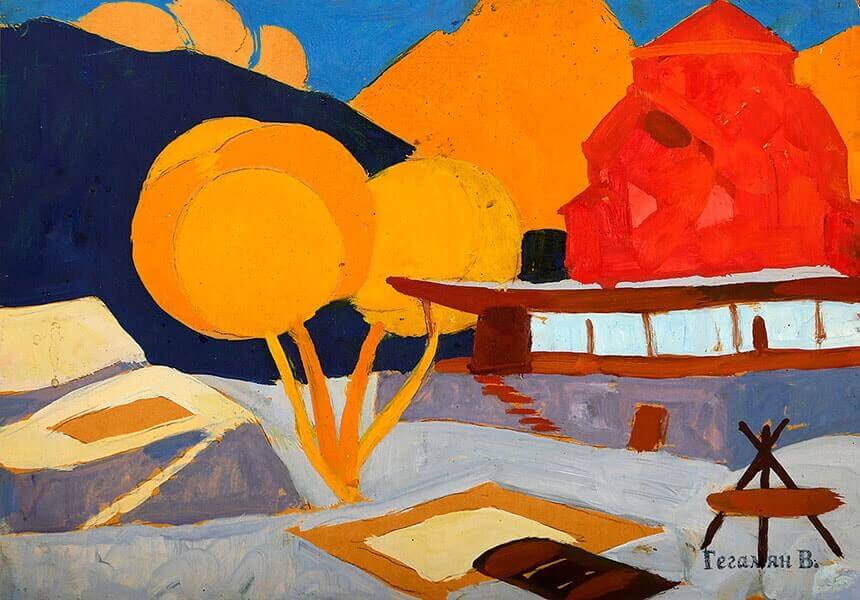

Surprisingly, in the diary of a nineteen-year-old boy, everything that he has to do in painting and graphics is described in detail and unambiguously. Starting from homage to the “color of Sarian and Gauguin”, “the divine triumph of Rembrandt” and to the mention of acute emotional states of nature, expressive presentation of thought, analysis of nature into its components.

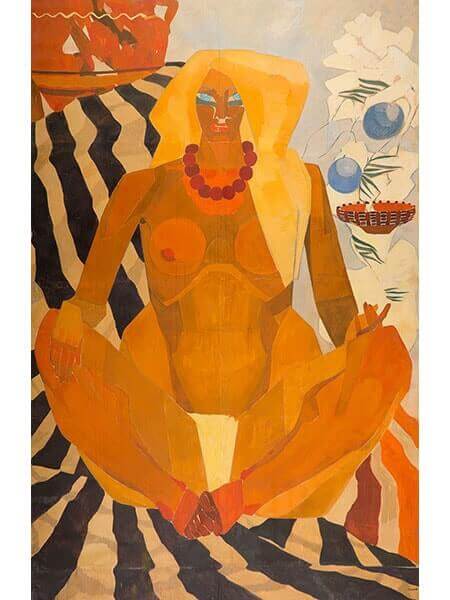

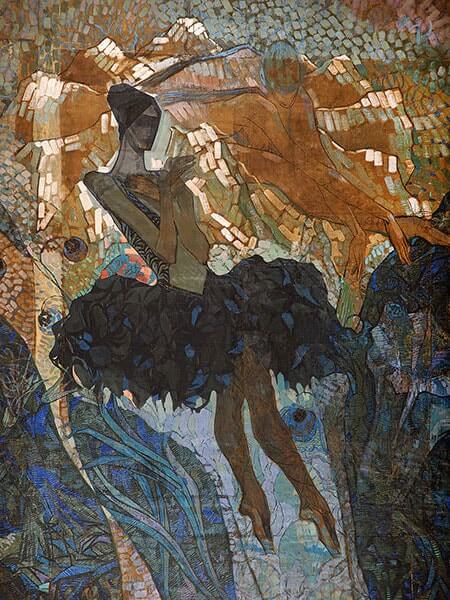

Even the luxurious rather late ballerinas saw the young man as already realized one in the distant 1944 - “... monumental portraits. Huge ballet canvases ... where the clothes are tight, as if the body goes out ...”

And what about huge, statically divine female images? How is it possible to write at the age of nineteen: “The center of life is a woman, and a human can live spiritually until a woman stops charming him, even in a difficult moment. Imagine a woman, if at this moment you can admire her, then you can live”? After all, this is not the romantic verbiage of a gentle youth, but the fully formed thoughts of a mature man.

Of course, the artist has changed throughout his career. Only it is unlikely that these are transformations, rather, he simply crystallized, discarded unnecessary and insignificant things.

Geghamyan brilliantly finished his studies at the Art University and real prospects opened up for him. Martiros Saryan recommends the young artist to Moscow as a senior master and then as a monumental artist at the Combine of Decorative and Applied Arts. The place was honorable, profitable, but unpleasant for a decent person: monetaryt orders, as a result – intrigues and machinations of fellow competitors. This time period contains the main mystery of Valery Geghamyan's fate – why did he leave from under the patronage of Martiros Saryan? What provoked a discord between them, as a result of which Geghamyan left the capital for the provinces for the modest position of a drawing teacher and never spoke with Saryan again?

Six years of the ordinary life of a Soviet intellectual in Birobidzhan and Makhachkala gave us several classic canvas / oil portraits, quite characteristic and very subtle and coloristically interesting, but, perhaps, slightly dull.

#302

In 1963 a significant event took place, in Makhachkala he met his future wife. As usual, according to the laws of the genre, at that time she was a stranger's wife, but this did not seem to be an obstacle to an emotional person. Deciding not to be content with a romantic story for inspiration, Geghamyan dramatically changes his life in one year and finds himself in Odessa with his wife and long-awaited son. In fairness, it should be noted that the initiator of the move was precisely Boleslava, a shapely Polish woman who had boundless faith in Geghamyan. Their union was strong with clearly defined roles: he is a genius, she is a genius of providing at genius. Igor Guberman's joke comes to mind:

So that the Artist could fully express

His soul vastness,

Two little things are needed: diligence

And a hard-working wife.

Boleslava took over the whole daily routine, everything that should not have distracted Valery from work. And he was very diligent.

Starting 1964 Geghamyan taught at the Pedagogical Institute, becoming the founder of the Faculty of Art and Graphics and for two years, until he found a replacement for himself, was a dean on a voluntary basis. Then he taught drawing, composition and painting to several generations of students. An impeccable draftsman, he “set” the academic drawing, jealously guarding the developments of his personal style which many years later would be called “the figurative geometry of Geghamyan”.

For all his integrity, he was clearly a man with follies, with a complicated character, with a clear system of principles and values. Often, such types are very easy to define with the word "wiser", but behind all this complexity was an extremely vulnerable person, unable to endure dishonesty. Distance for such people is the only way to somehow exist in society. Geghamyan's desire to "not touch" acquired truly grotesque forms, he literally did not touch - he even opened the door with a handkerchief and at an unattainable height, "where no one touched." He also breathed through a handkerchief fearing unknown germs.

In the lecture room he was a polite despot, not allowing himself temperamental tricks, but, nevertheless, demanding from students unquestioning obedience to his pedagogical methods. The doors of the lecture room were latched five minutes before the start of the class, pencils were subject to the maestro's personal inspection, breaks were ignored as an unnecessary luxury. But Valery Arutyunovich himself worked fanatically. This is the clearest example of an honest attitude to one's profession, where there is everything - talent, skill and daily work, and uncompromisingness.

Geghamyan as a teacher is a separate story. He himself did not claim to be a teacher, because he was in love with painting, but had a unique gift of an individual approach. He was laconic in his statements almost never criticized. When exhibitions of student works were held at the faculty, Geghamyan came early in the morning, never said anything. But if he liked the work, he lingered beside it and involuntarily adjusted his belt. This movement was something of a positive characteristic.

Contrary to the conventional thinking that any original Odessa artist is certainly a nonconformist and a Protestant since he was born, Geghamyan never tended to the underground. Perhaps he did not even know about its existence, he had something to do in the classroom and at home and at the plein air with students in the Carpathians and Crimea. He completely ignored exhibition activities, had little interest in any organized artistic expression, both official and unofficial.

Of course, due to the specifics of his work, he was forced to participate in endless meetings, conduct ideological educational conversations and so on. But today you understand that it was all some kind of parallel reality in which people formally existed, because it was a condition of their professional activity.

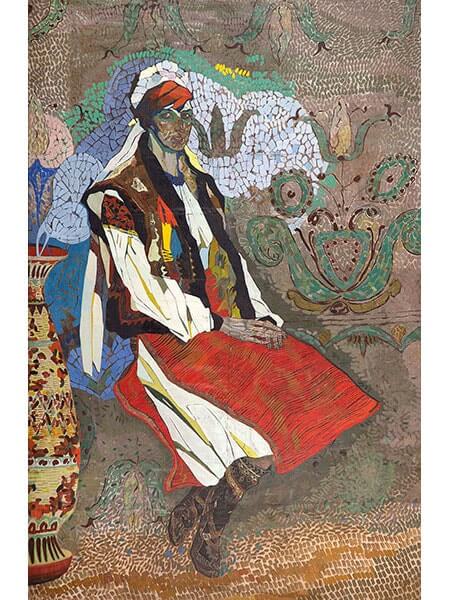

Life in Odessa was not easy for the Geghamyan family: housing problems, problems with promotion, small income. However, they say that a roof over their heads often prevents people from growing. Valery Geghamyan never got his own workshop. He created his monumental works in a small apartment, stitching canvases and gluing sheets of cardboard into huge planes, reshaping them many times and layering them on top of each other. Often he created paintings in fragments since the entire gigantic format was “out of the format” of his apartment while demonstrating crazy spatial thinking, never making a mistake in proportions and foreshortenings. All the more surprising - after all, he has never seen his works from the exposition distance. In scale and refined convention raised to the highest dignity, Geghamyan's works are on a par with the works of Jose David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco.

It is generally acknowledged that he worked on cardboard because these were only preliminary sketches for the monumental final images in other materials and techniques. This is partly true; it is worth recalling the sketch of the mosaic in the studio “Berezka” (1963). But it is so only to a certain degree. Most of the works are independent works. Most likely it was just convenient for the artist to work with cardboard, because he often changed the format and composition. Gluing or cutting cardboard is much easier than stitching or cutting canvas.

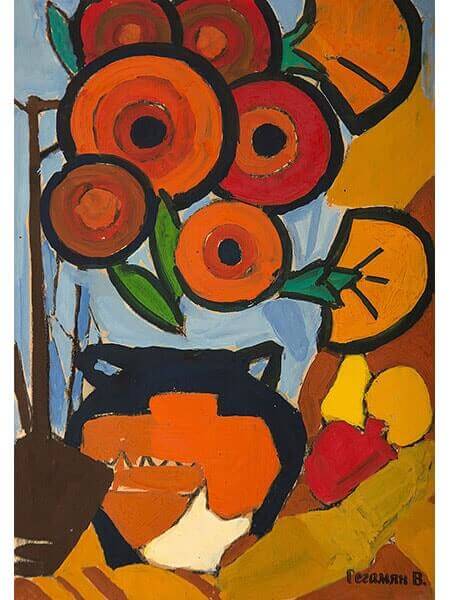

Geghamyan's works by genre are represented by an almost complete classical set, from the dissection of masters’ paintings (Vrubel, Saryan, Korin, Altman), from still life paintings and landscapes, portraits (conventional and quite specific) to large-scale thematic paintings concerning the "universal significance."

Strangly, but for all the sociopathy of Geghamyan the personality, the main thing that interests Geghamyan the artist is a human. Firstly, an individual, then laconic, decorative-conditional type. Human as nature, as spirit, as a state, aspiration. Truth, judging by his works, Geghamyan did not really believe in a human, in a woman – perhaps, yes. In a human – not so much. Here and there a despair is visible, bordering on doom. He cannot find a humanistic hero-optimist and he is not needed.

#384

After retirement in 1985 Valery Geghamyan, according to his student Valentin Zakharchenko, said: "The time has come for an artist." It's funny how this thought echoes the words from the old diary: “Finally stop imagining. We must create. "

From now onward and until the end of his life he worked every day for 12 or even 16 hours. It was a time of voluntary reclusion and hard work, mostly unnoticed by anyone except the family. Sometimes Geghamyan went to Lanzheron and observed people. Probably, he was looking for typical types there for his multi-figured compositions. Being in such modest living conditions and cramped life circumstances, not paying attention to the lack of understanding, lack of prospects, and at times, frankly arrogant or sarcastic attitude, Geghamyan never complained. You can be as talented as you like, have many professional merits, but one day multiply all this wealth by zero personal dignity. Or - to do something all life, once and for all deciding that this is what is important.

Geghamyan wrote "... it is necessary to try to get more numerous, healthy, human impressions." Life has kindly provided him with not only healthy impressions, but after all according to Merab Mamardashvili, a world-renowned Georgian philosopher, any impression that strikes the soul is light. Well, these rays of light were dissected, decomposed into colors and then reassembled by Geghamyan, as a pathologist, but already in his visual-geometric compositions.

In June 2018, thanks to the initiative of the artist's grandson, Maximilian Geghamyan, the Valery Geghamyan Prize will be awarded for the second time. It is an award in the field of visual arts that is awarded annually to artists whose work is an example of selfless and altruistic service to the arts.

1925 – Valery (Valik) Arutyunovich Geghamyan was born in Garni, Armenia.

1940-1944 – Art School, Yerevan.

1945-1950 – Yerevan Art Institute, workshop of Martiros Saryan.

1954-1956 – a leading artist in monumental painting at the HF USSR in Moscow.

1956-1960 – teacher at the pedagogical school, Birobidzhan.

1960-1963 – Lecturer at the Dagestan Art School, Makhachkala.

1964 – moved to Odessa, worked in the Odessa branch of the Ukrainian SSR art fund.

1964-1985 – teacher of the graphic arts department at Odessa Pedagogical Institute named after Ushinsky.

1985-2000 - reclusion in creativity.

2000 - died and was buried in Odessa.